Spring Deliverable

As part of the University of Virginia’s Spring 2017 graduate seminar on Transport Layer Security (TLS), our project team has continued to investigate modern issues surrounding usable privacy and security of web browsing. The Line of Trust project seeks to understand the security, privacy, and human-factors related to a class of phishing and picture-in-picture attacks known collectively as the Line of Death. Contextualizing relevant literature and systematically analyzing the underlying problems in the Line of Death space will contribute to a Systematization of Knowledge (SoK) paper, which we intend to augment with a thoughtful user study. The goal of this blog post is to present the culmination of our work throughout the last six weeks of the semester and provide a roadmap for our team’s plans to move forward through the summer months.

Presentation

TLSeminar’s mini-conference provided our team the opportunity to motivate and present our project work during the latter half of the semester. Our presentation (above) focused on describing the research problem through a case study of an elaborate picture-in-picture Microsoft Support Webpage Scam reported in March 2017.

Introduction

The state of web browser client UI today is best described as a disjoint medley of vulnerabilities, contradictory design principles, and implied security conditions. Apart from the overarching design paradigm of a URL bar perched above page content with a tab-interface situated nearby, almost all aspects of contemporary web browsers vary from one vendor to the next. There exist no universal security indicators, nor are the relative levels of security—think mixed HTTPS vs full HTTPS—ever explicitly presented to consumers of these products. Warning prompts, pop-ups, and alerts are all handled differently. Settings are difficult to find. Extensive assortments of flags, optional settings, and advanced content featuers are tucked away far beneath the visible surface of the browser interface.

This industry-wide abuse of basic UI principles has resulted in a number of frightening security implications for everday users—issues that have largely gone unaddressed in the security community for the past decade. Though major vendors like Google (developer of the Chromium project and the Chrome web browser) have taken steps to address some of the more sophisticated UI security issues plaguing web browsers, much more must be done to provide a sense of security for the vast majority of average Internet users who are most vulnerable.

This post is the result of six weeks of brainstorming, reading, contemplating, presenting, and discussing web browser UI security. In it, we seek to provide a framework to systematize current and proposed approaches aimed at improving web browser client UI, venturing as far as offering a few suggestions of our own.

Before we delve into that, however, some motivation is in order.

The Line of Death

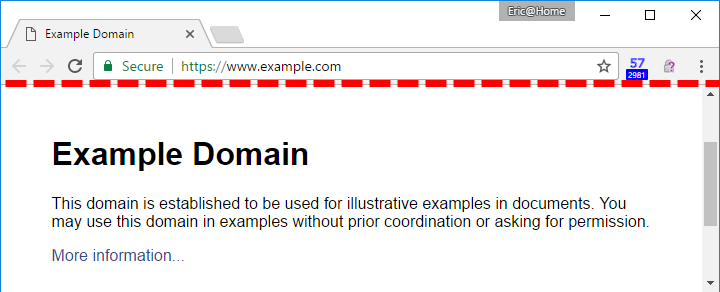

In January of this year, Eric Lawrence, writing for text/plain, published an article about an intriguing concept he coined the “Line of Death” that demarcates trusted from untrusted content in a web browser. Consider the image below.

As you can see, the page, www.example.com, exercises full control over the content below the red dotted line—the “line of death.” Consequently, as a user, you should not trust anything below this line that appears to be imitating a legitimate browser function. For example, consider a malicious page attempting to redirect you to a spyware site. The page may generate a fake element that looks like a generic “alert” box, but since it appears below the line of death, the user should assume that it may be fake and thus refrain from clicking. As one would imagine, this notion is problematic—real alert boxes actually do appear in the untrusted page content! How are average users expected to differentiate between legitimate alerts hovering above the browser window and fake alerts displayed within the browser window? Making matters worse, malicious developers can even deploy JQuery scripts that cause their fake alert boxes to mimic the UI functionality of legitimate boxes—click and drag, “cancel,” etc. This mimicry is not limited to alert boxes; page elements such as download prompts, microphone/camera permission prompts, and plugin prompts are all vulnerable to imitation.

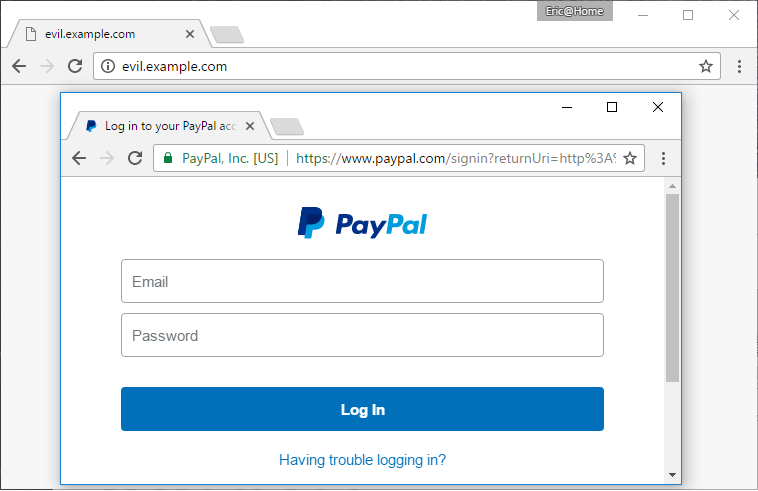

We can extend this basic line of death example even further by imaging a scenario in which the entire trusted UI —tab bar, URL bar, bookmarks, HTTPS status—are spoofed within the untrusted content area. But that would be so obvious, you exclaim! Well, as we shall see, this so-called “picture-in-picture” attack is most potent when the user enters full-screen mode, wherein the trusted UI portion disappears from view to provide the user with more screen space. An unsuspecting user could easily forget that a URL bar should not be present and simply trust the URL bar and security indicators that happen to be dispalyed in the spoofed UI. For example, in the image below, the entire legitimate, trusted browser UI one would expect to see while visiting PayPal.com is spoofed and displayed inside the untrusted content area.

Certified Malice

In a follow-up piece to Line of Death published only two days following the original article, Eric Lawrence presented another, more insidious browser UI weakness: malicious websites can just as easily acquire HTTPS certificates as legitimate websites. This so-called “certified malice” renders the identification of illegitimate spoofing sites nearly impossible. In this threat model, phishing sites attempting to masquerade as legitimate sites “secure” their pages with HTTPS certificates, leading users— generations of whom have been trained to trust the green lock —to believe the malicious site is “good.” (We cannot help but point out the obvious irony: HTTPS certificate proliferation helps the bad guys, too!)

Clearly, this intricate web of UI, security, and social engineering issues necessitates attention to ensure average web browsers do not go astray attempting to check email online. The two articles referenced above were published less than four months ago and represent the only contemporary inquiries into web browser UI problems. In fact, it seems that most serious academic work in this area ceased about ten years ago. This abrupt end to the study of web phishing attacks could mean one of three things:

- Web phishing is a hard problem with few clear answers, therefore it’s difficult to be published, hence the lack of published papers.

- No one cares about web phishing anymore. It’s not cool.

- The research community has been focusing on other pursuits in the past decade but would certainly investigate these issues if given a friendly reminder.

We maintain a firm belief in option #3, and in the potential for future investigation and academic work. This systematization and roadmap seeks to codify that belief.

Systematization

Overview

Our systematization follows a uniform process that enables us to categorize, assess, and ultimately rate the potential usefulness of various research works and related resources. In it, we attempt to address the following issues:

- What problem(s) does the resource address?

- Does the problem relate to web browser UI? If so, how? What aspects of the problem are shared between the resource topic and web browser UI?

- What solution(s) is proposed?

- Are the solutions relevant to web browser UI? If so, how? What aspects of the solution(s) could be applied to web browser UI?

- What are the pros and cons of the solutions with respect to security, usability, and ease of adoption? Will people use it? What security guarantees are implied? How likely is it that users will actually interact with the solution mechanism?

- [if viable] Based on the resource, how would you suggest proceeding with the implementation of the solution?

A Trusted UI for the Mobile Web (2014)

The population increasingly relies on mobile devices to browse the web. However, just as there is a distinct dearth of work focusing on web browser user interface design with respect to security, the literature covering this sub-space is shockingly sparse. Not only do mobile devices confront new, additional challenges, but mobile web browser user interfaces still face the same security challenges as those faced by web browsers. Braun et al. do a notably thorough classification of a set of major threats to web browser security, for both full and mobile web browsers alike. These threat classes are phishing, clickjacking, CSRF attacks, XSS worms, and session fixation. Briefly, the goal of a phishing attack is to convince the user to divulge personal information. Clickjacking occurs when an attacker misleads the user to unintentionally click on an unseen icon or button by clever use of JavasScript. CSRF attacks involve a crafted URL that causes the browser to send a request to the web application on behalf of the user. XSS attackers insert malicious code into otherwise benign websites, which then can run without prompting. In a successful session fixation attack, the attacker sets an SID before logon, then accesses the user’s session simultaneously to the user, impersonating them.

Furthermore, mobile browser security is also challenged by problems unique to mobile devices. Smaller screen sizes leave less space for visual security indicators; to the point, most major mobile browsers today default to hiding the entire browser bar. This leaves the bare contents of the page unaccompanied by status elements like the site URL, which are vital for users to visually verify the identity of websites. Another important user-side security vulnerability introduced to mobile devices is the tendency for users to create shorter, easier-to-type, but less secure passwords, chosen because of clunky, difficult virtual keyboards onboard mobile devices. Finally, “tapjacking” is the mobile variant of clickjacking threats. This is essentially clickjacking on mobile devices; given the limited space on a mobile device, tapjacking can be accomplished by zooming clickable zones even a small amount. For example, Iframes, Apple’s frame-defining software, can be overridden by attackers to achieve this goal.

This classification of threats, for full and mobile browsers, mark out common vulnerabilities of the user interfaces. Since these threats attack the path between the user and the browser, the burden of responsibility to provide defense is placed on browsers. Thus, to secure users against these threats, it is vital to establish more meaningful user interfaces and explore thoughtful alternatives to approaching to the way users interact with the web. In particular, keeping users out of the path of danger is primarily important when users are performing authenticated actions online. In these cases, where users are attempting to log into a website with private credentials like usernames and passwords, there is a particular need for a trusted path that verifies the user’s intent in order to convey this sensitive information.

Braun et al. introduce an alternative to entering user credentials directly into browser forms. On mobile devices, when a user tries to perform an authenticated action by accessing a page that requests their credentials, this request is routed through a dedicated app, distinct from the browser application. This app encapsulates user’s credentials and authorization state and maintains a trust relationship with the web server. Once the user passes a security challenge prompted by the app, the user’s authority is passed to the server-side module using a Diffie-Hellman-style shared secret. Thus, the browser app itself never receives, processes, or sends credentials that are used to conduct authorized actions.

While not explicitly discussed by the authors, a similar solution could, of course, be implemented on non-mobile browsers through a browser extension or distinct application, as the challenges faced by standard browsers is a subset of those faced by mobile browsers. Regardless of the platform, this solution not only creates a trusted path to convey the user’s authority between the user and the web server, but more importantly, addresses the discussed threat classes like phishing or clickjacking. If a user enters an illegitimate page posing as a familiar, trusted site, the authentication app will not recognize the server’s identity, and thus, will not pass on the user’s credentials.

The primary advantage of this proposition is that it does not rely on the web browser user interface to stopgap its persisting problems with an arms race of creating more conspicuous alerts or modifying spoofable visual elements. Instead, it augments web browser user interface design by relieving it of the task to relay user authority to the server. In turn, this process bypasses the vulnerabilities that come with sensitive user information being passed through the browser, like phishing attacks. It also does not rely on the user paying attention to visual security alerts produced by the browser or being observant enough to notice a suspicious site posing as some other trusted site in an attempt to steal their information. Furthermore, variations of this solution have already been deployed to the market with great popularity: for example, password managers like LastPass save the user’s credentials in one master account for web and mobile, guarding them with options like two-factor authentication, fingerprint scanning, or a master password. These services also often provide strong password generation, reducing the tendency to reuse passwords or create weak passwords. Overall, this also increases browser usability, allowing users to use more secure passwords without the inconvenience of remembering and retyping them.

Moreover, more analysis is required with regards to security; new or continuing threats to this proposed solution need to be thoroughly explored and evaluated. Whether or not the app request itself is spoofable seems like it would be a significant factor in the potential for adoption. The applications also need to be set up in such a way that users still have the ability to enter their credentials on unauthenticated sites if they choose to. There may also be higher-level questions that are worth asking; for example, does requiring a server-side module, which could perhaps limit the use of password managers to popular sites, threaten net neutrality?

Trusted Paths for Browsers (2002)

Zishuang et al. attempt to define a system for differentiating content elements, which make up webpages, from status elements, which lie in the browser bar and indicate meta-data like the URL. As it stood at the time of the paper’s publication, no significant differentiating features existed to give users a trusted sense of where a given element is coming from. Users can be tricked by false spoofed browser elements, and providing a way for them to identify true status elements would greatly support user interface security.

This inability to distinguish notification sources leaves users susceptible to clickjacking and phishing attacks. A common solution to this problem is to change the visual appearance of the browser in an attempt to prove to users that it is authentic. In this vein of thought, Zishuang et al. propose and evaluate a variety of potential visual browser authentication solutions to this problem. The potential solutions are assessed on a binary scale based on inclusiveness, effectiveness, minimization of user effort, and minimization of intrusiveness. Respectively, these categories are meant to ensure that the system makes the sources of elements both broadly and usably identifiable, requires little effort or disruption on the user’s end, and does not cramp usability.

Zishuang proposes and attempts to evaluate a variety of potential solutions to this problem. The potential solutions are evaluated on a binary scale based on inclusiveness, effectiveness, minimization of user effort, and minimization of intrusiveness. Respectively, these categories are meant to ensure that the system makes item sources broadly identifiable, usably identifiable, require little effort on the user’s end, and not interrupt or limit the usability. The style selected as most useful by the paper is SRD, or synchronized random dynamic boundaries. SRD was evaluated positively in all four categories.

The target goal for all solutions is preventing collisions between browser and content spaces, just like the elements above the “line of death” is meant to be browser-only. One proposed solution is called “no-turnoff”, which simply prevents features like fullscreen from effectively turning off status elements. This was rejected on the basis that it infringes on a significant amount of content and would be rejected by the internet community. Furthermore, modern mobile web browsers rely on being constantly in semi-full-screen mode.

Another solution hinges on user-specific customized indicators that would require some input from users at browser outset. This was generally found to require too much effort on the user’s end and would lead to problems like overused passwords. Users also may not notice or recognize such content (or the lack thereof) in browser/server notifications, so too much of the responsibility is put on the users to be aware of threats. Other efforts fail in similar ways, such as creating metadata titles and windows. In these cases, information would be passed through “safe” means to the users, but still requires that users check for this data before proceeding with anything. The “safe” data spaces would either be in the title, which is subject to picture-in-picture attack, or in a separate browser window, which will likely be ignored altogether.

The CMW approach is discussed in depth, creating a secondary colored browser window below the main window, indicating the safety of page content. Theoretically, by pairing this with a boundary-style solution, users would be able to identify attacks like picture-in-picture based on inconsistencies between the boundary color and the secondary window color. This was rejected because it requires that the user clicks on the potentially unsafe content before being able to confirm the safety of the content. However, SRD, a subset of CMW-style solutions, was evaluated as the best solution by the authors, according to their criteria. In an SRD-active browser, the border color of the browser and the color of the secondary window would change in a random but synchronized manner. The hope was that attackers would not be able to spoof these random changes, and color discrepancies would be relatively easy to identify by users. Note that this require both the secondary window and borders to be fixed on the screen, visible even when full-screened.

In context, the propositions in this paper represent a family of possible solutions to securing the user interface of web browsers, which all focus on improving visual security cues, in an attempt to enable the user to notice when an illicit third-party spoofs their webpage. CMW-style solutions and others mentioned in the paper come from an older era of browsers, and are thus, not easily applicable to mobile devices or perhaps even modern web browsers. In the event of attempting to implement particular ideas, backing by popular browsers would be unlikely and implementation issues arise. For instance, Firefox currently prevents scripts in non-active windows, meaning that the secondary window that provides the reference color in the SRD solution would freeze at its initial color until the user switches windows, so synchronized random color changing would be impossible.

More generally, there are two primary issues that arise for this solution approach. Firstly, they expect users to be vigilant, placing a burden on the users that should be carried by the browsers. Secondly, any attempt to authenticate browsers visually using positive security indicators is spoofable. Instead, rather than attempting to identify safe elements to the user, a more promising route along these same lines of using visual attractors is the concept of actively showing insecurity.

Your Attention Please (2013)

When analyzing the effectiveness of visual security indicators, there unfortunately arises the “boy who cried wolf” problem which currently faces browser user interfaces today. In contemporary browsers, users are inundated with excessive warnings, which, dangerously, desensitizes them to alerts of real risks. When deciding whether to visit insecure sites while browsing, it is essential for browsers to convey security messages that are effective, meaningful, and minimally disruptive. The user study conducted by Bravo-Lillo et al. evaluates the ability of particular types of warning elements to cause users to deviate from their “script”.

The paper presents and assesses five inhibitive attractors, which draw the user’s attention to important details, and either allow time to expire or require user interaction to proceed to the requested action. For example, the site URL might be highlighted in yellow or the user might be required to type the site URL into a dialogue before proceeding to the page. Their effectiveness was then tested in a user study for three different scenarios, and Bravo-Lillo et al. found that among 872 participants, their proposed attractors outperformed the control by up to 50%. These results suggest that alerts that prevent quick warning click-throughs or require user interaction are helpful for preventing users from exposing themselves to security vulnerabilities.

The study captures an important principle of web browser UI design: to avoid strong-arming users out of performing actions which the browser deems unsafe, while still protecting users from themselves. Put plainly, users should be able to do what they choose to do, rather than have this choice taken from them. Thus, it is paramount that browsers enable users to make an educated decision, which requires the browser to provide the user with intelligible security indicators. These messages need to consistently capture the user’s attention and convey the specific, real-life dangers of bypassing the alert.

While the specifics of this particular software implementation studied in this paper are not necessarily directly applicable, implementing similar indicators for user actions would be potentially useful. For example, when typing in a password field, prompting the user to interact with the browser URL in some way could help protect users from phishing attacks. More importantly, the principles of these attractors could be helpful for conveying vital security information to the user, like an insecure site.

You Can’t Be Me: Enabling Trusted Paths & User Sub-Origins in Web Browsers (2014)

An important threat class in browser security is post-injection script execution (PISE) attacks. Budianto et al. attempt to address scripts that are injected into a web session (malicious scripts included) after the user is authenticated that have complete access to user-owned resources. Web applications that provide services to users with accounts, such as email services, social media, or online banking, restrict access control using the notion of user authority. Usually, this access is governed by the same-origin policy, which allows servers to only permit scripts originating from the site itself to modify pages. However, this is insufficient in PISE attacks, because injected scripts can appear to the web server to come from the same origin as user input, with the same protocol, host, and port. Thus, server-side web applications cannot distinguish between the real user’s requests and requests generated by scripts.

Web browsers are charged with the difficult task of providing a trusted path between the user and the server. Since this stream can be poisoned en route to the server by PISE attacks, it is up to the browser to guarantee that user authority passed through the browser user interface is not abused by illegitimate third parties. Thus, there is a need for an improvement in the way the web browser user interface handles the user’s authority.

Budianto et al. define user sub-origins as all primitives that run with user authority. Using this concept, they propose User-Path, a protocol that establishes an end-to-end trusted path between web browser users and web servers by isolating the user’s data and privilege from the rest of the web origin. Thus, User-Path tightens the authority of users from the entirety of web sessions to user sub-origins. This is accomplished by refining the web-browser’s user interface by providing a secure tunnel to relay user data to web applications, despite PISE attacks like XSS worms.

Since this solution is a very light extension (the authors report their implementation is less than 500 lines of code), it appears very deployable and easy to adopt. Furthermore, usability remains unaffected - the implementation increases the security of the user’s authority without changing the user’s experience on the front-end. However, this is a limited solution which addresses the particular problem of PISE attacks. User-Path is not a comprehensive defense against all threat classes in the field, but remains an important smaller element of a greater-encompassing solution.

Work towards implementation has been started; Budianto et. al have already developed a Chromium patch. Future work includes extending similar versions to other major browsers and potentially making it a default browser component.

Operating System Framed in Case of Mistaken Identity: Measuring the success of web-based spoofing attacks on OS password-entry dialogs

Today’s desktop operating systems often use windows which provide scant evidence that a trusted path has been established when asking users to enter credentials (Bravo-Lillo, C., et al.). This paper attempts to quantify the success rate of web-based spoofing attacks on OS password-entry dialogs. There is a clear connection between this study and common Line of Death browser UI attacks, as many of them rely on emulating valid browser- or OS-level elements to trick users into clicking on links or entering sensitive credentials. The study validates the efficacy of web-based attacks that spoof OS windows and presents the challenges of a path forward to trust: “proving that a trusted path ritual will resist real-world attacks requires deploying the ritual into the hands of users who will be relying on it to do so. The failures of individual trusted path mechanisms suggest that the problem is unlikely to be addressed adequately by any single mechanism. Rather, future work may focus on rituals that combine mechanisms. For example, consider rituals in which users must first enter a shared attention sequence and then expect to see a visual shared secret.” There remain significant usability concerns of any particular trusted path implemented, although it is clear from the study that is Line of Death attacks are highly successful and readily feasible on unsuspecting users. See our user study design considerations for further directions inspired by this study.

GuarDroid (Trusted Path, Authentication)

GuarDroid is a system that protects Android user’s passwords from untrusted Android apps. It addresses the problem of establishing a trusted path between the user and the service that leverages the smartphone operating system as a trusted computing base. In relation to web browser UI privacy and security, GuarDroid presents a means to “invert” the relationship of user authentication to web sites by keeping the Android operating system accountable for verifying itself to the user; the user is not intended to trust sensitive input forms that are not protected by GuarDroid’s application overhead, and only to trust GuarDroid’s input when presented with the secret passphrase set prior to the smartphone’s system image configuration. While GuarDroid is designed to leverage security guarantees for untrusted Android applications and their form data submission to web servers, the applicability of GuarDroid to a web browser UI (perhaps executed through a trusted extension or core browser feature) is analogous to the scope of the Line of Death attacks we consider. The most significant deterrent to using GuarDroid’s trusted path is the usability need for the secret passphrase to be a human-readable phrase (i.e., low entropy for a guessing adversary) rather than utilizing random base 64 characters as the secret for verification. The advantages of implementing a trusted path, however, are quite effective and serve as a model of a solution to picture-in-picture attacks from the trusted base of the browser.

Rethinking URL Bars as Primary Browser UI

In this work, Google employee Owen Campbell-Moore argues that the browser URL bar provides users with antiquated information and delivers a call-to-action for overhauling browser UI. This piece is of particular interest to the systematization since it directly addresses browser UI, and the solution proposed—overhauling browser UI by removing the URL bar and replacing it with an origin-to-local-brand-mapping interface—would greatly alter the browser security landscape. According to Campbell-Moore, URL bars exist to perform three basic tasks:

- Provide the identity of the site being visited (domain name, title tag)

- Indicate relative location in the site organization (path)

- Provide an easy-to-share resource link (URL)

Tasks (1) and (2) are increasingly unnecessary, since most users rely on search engines, apps, bookmarks, and history to navigate to destination sites. As a result, there are fewer opportunities to manually provide URLs, and as mobile browsing continues to decimate client browsing, there will be even fewer. The user’s current path location on websites is used even less, especially given the proliferation of dynamically generated “app-like” content of Web 2.0. In fact, Campbell-Moore argues that only (3) is still legitimate, but even that is being replaced by the ubiquitous “share” buttons connected to various social media entities.

Origin-to-local-brand-mapping would operate in a manner similar to DNS or certificates, in that an “identity” is mapped to a resource, except in this case, the identity would consist of a name and a logo. The idea would be to only provide this mapping to certain “well known” web sites, thus avoiding the scenario in which a legitimate site registers for the mapping service. As a result, it would be very obvious to casual browsers whether they have arrived at the real PayPal.com or not, since the real PayPal.com will come with an origin-to-local-brand-mapping that clearly signals its legitimacy.

Obvious concerns include the notion of compiling and maintaining a “well-known sites” index, since at face value, this seems to violate neutrality and place a vast amount of power into one organization’s hands (likely a search engine, likely Google).

Phishing

Motivation

In March 2017, Tripwire reported on a phishing scam that claimed to be a Microsoft support page. Victims of this scam were presented with a virus warning in a popup over the fake support page. The page proceeds to enter full-screen mode, appearing to the user as an entire browser window with rendered page. Thus, the page itself displays the browser header, although a user will assume that this header belongs to the browser itself. The only evidence that the browser header in view is fake is the default browser’s warning for full-screen mode. Sophisticated Line of Death attacks such as this are becoming increasingly used for phishing.

Attack types

There are several targets of web browser UI spoofing attacks. These can broadly be categorized into attacks against the identity of the server being accessed or attacks against the operating system windows. In the latter, the page renders elements that mimic popup windows from the operating system, usually with the intention of asking the user for escalated permissions. However, since the human-centric aspect of Line of Death attacks is similar for OS and server spoofing, we primarily consider the server case. Server spoofing typically targets the identity of the server, attempting to convince the user of its authenticity. The classical Line of Death attack for spoofing user interface elements is the picture-in-picture attack, in which the page contains fake browser elements such as the header. The Microsoft support page spoof discussed above is such an attack. More specific attacks can attempt to spoof the connection and appear to use a TLS connection to the intended site, while in reality the connection may be unprotected or may connect to a malicious site.

Solution principles

Literature in the area of browser spoofing protection has yielded several guiding principles for effective solutions. These principles define the qualitative behaviors of effective solutions and account for user behavior.

1. Solutions should require minimal user effort. Browser users have widely disparate backgrounds in web security and cannot be relied upon to understand extremely specific security warning messages. Furthermore, the nature of Line of Death attacks exploits limitations in human perception, and can often fool even seasoned security experts.

2. Solutions should be all-inclusive and easily identifiable. Graphical solutions should be easy for users to recognize and solution approaches should address many different kinds of attacks.

3. Solutions should not be intrusive. Browser users are more concerned with the content they are trying to reach than security warnings, and excessive warnings will annoy users and desensitize them to warnings in general.

These principles are subject to the security vs. usability tradeoff. Increased security warnings and indicators may alert the user to threats but may simultaneously degrade the user experience.

Approaches

There are various approaches for resolving browser UI spoofing. These approaches can be evaluated based on the principles above. No approach is perfect, but their strengths and weaknesses inform new areas of approach for solutions. These approaches are largely based on the concept that the browser must distinguish between the content and status (context, connection, server) of the page.

One approach is to never allow browser status information to be turn off. With this approach, status information is always visible to the user while the browser is running, allows a user to always know the identity and nature of their connection to the site they are trying to access. Although this provides a consistent source of information to the user, this display can be obstructive to webpage content and may harm the user experience.

As an alternative to constant indicators of security status, the browser can request a certain degree of customization for the user’s browsing experience. Customized UI features provide familiarity, and by extension, trust. Browser elements that can present the user with customized features can therefore authenticate itself to the user by presenting the user with a secret (customizations) shared between the user and the true browser. However, this approach requires the user to consistently look for these customizations and recognize that the lack of customizations is an indicator of danger. Abstractly, this means presenting a user with a lack of a security icon to indicate threats. This cannot be guaranteed (or even expected) from most users.

The title and header bar of the browser can be modified to present metadata about the site and connection associated with a browser tab. For example, the true URL for a connection can be displayed on the window title. However, this can be easily spoofed by a targeted phishing site, since the metadata title can be rendered as part of the page. A similar approach involves entirely separating content from the metadata by presenting the metadata in a separate browser window.

Tools

Researchers have developed various tools that utilize these approaches to attempt to resolve the Line of Death and related browser UI spoofing.

One such tool is SpoofGuard, developed at Stanford University in 2004. SpoofGuard adds a browser bar indicator with green, yellow, and red lights. These lights serve as a ranking of threat level for any page that the user visits. SppofGuard performs 2 rounds of checks on each page: the first is performed before navigating to the page and the second is afterwards.

During Round 1, SppofGuard examines static features about the site, such as the domain name (as well as edit distance to known common domains), URL, and email fields. These features are evaluated according to a pre-developed heuristic to determine a threat score for the page.

Round 2,which takes place after the page has rendered, examines elements, such as password fields (especially those that are unencrypted), links, and images. These features are similarly combined through a heuristic. In addition to password fields, Spoofguard also tracks password usage and warns the user before submitting passwords to dangerous sites.

However, SpoofGuard does not defend against determined attackers - it only makes it more difficult to set up a fake site. Search engines could also mitigate the problem of spoofed URLs through an automatic Google search and then comparing Google results to intended sites.

Active insecurity

One overarching theme related to the approaches and tools presented above is that most tools attempt to actively present indicators of security. Symbols such as green locks and shields inform the user that the browser state or display are secure. This informs the existence and location of trusted browser elements. However, active security indicators can be easily spoofed by phishing sites that also present these indicators. In contrast, presenting active indicators of insecurity, rather than security. This could be warning indicators of insecurity in place of positive security indicators. For example, if a red border is placed around insecure elements, the page content cannot easily modify this insecurity indicator to instead establish trust with the user. This approach to security UI needs more examination in the research community.

Deliverable Conclusion and Project Roadmap

In this blog post, we first motivated and described our semester’s efforts towards the Line of Trust project, using our class presentation slides and a compelling case study. Secondly, we detailed and evaluated our methodology for systematizing research literature and community blog posts of significance to the Line of Death class of attacks. Thirdly, we coalesced and analyzed a variety of literature according to our systematization techniques, and constructed general relationships between the class of problems uncovered in our literature systematization.

As the semester is coming to an end, our plans for the future of the project are as follows:

We intend to continue work on the Line of Trust project during the summer months, with the goal of submitting a qualitative Systematization of Knowledge research paper to a conference in the fall term.

Given the difficulties encountered in uncovering reputable, relevant academic work in this particular area of interest, we hope to incorporate more resources into this systematization in order to provide a more holistic view of the state of web browser UI.

Design Considerations: User Study

Designing a thoughtful user study related to security is not a trivial undertaking. As Gaw et al. and Dourish et al. argue, user practices related to security need to be understood, yet actually obtaining observational data about the nature of user practices is challenging, since security is rarely interacted with directly.

Qualitative techniques such as interviews and surveys can be successful but have a unique array of limitations—namely, participants exercise heightened vigilance and caution and claim to take particular actions with respect to security that may otherwise be totally different outside the interview. Thus, the issue of unreliability becomes a limiting factor in the effectiveness of interviews and surveys. Interestingly, Whalen and Inkpen note that in a lab study of web browser security, participants didn’t act to protect data and resources as if they were their own, hinting that motivation is another area of concern in hands-on study approaches.

Lastly, the nature of conducting a study on security practices unavoidably introduces bias into the results, since the evaluator must somehow prime the participant to focus specifically on security, as Wu et al. note. Thus, a good security study must make security a peripheral goal rather than a primary goal.

We believe a web browser UI user study must seek to answer a series of questions:

Can users differentiate legitimate UI from spoofed UI? To answer this question, users will need to differentiate between fake UI elements generated in the page below the line of death and legitimate UI elements that happen to be overlaid on untrusted content. Though an outright comparison survey would be useful, many of these spoofing attacks rely on users missing subtle visual cues—cues that they would be highly attuned to while conducting a survey. As a result, identifying fake versus legitimate UI elements must be a secondary, passive object built into some other test. In effect, we need to mislead the study participants so that they are’t paying explicit attention to visual UI cues, but instead interacting with them naturally.

Can users detect picture-in-picture attacks? A similar approach to (1) is desired here—the users can’t know what is going on. This would gain added legitimacy if it were tested on both mobile and desktop browsers.

Do users understand what security or privacy guarantees the green TLS “lock” icon implies? How well do web users understand the concept that a malicious page with a secure connection is still malicious?

The experimental answers to these questions would help us determine whether this is, in fact, a serious problem that users are vulnerable to, rather than a niche phishing concern with little practical relevance in reality.