Status Update - Week 2

Motivation & Goals

User interfaces are vitally important components of overall security, bridging the gap that exists between system designers, security experts, and the end users for whom the systems are being designed. In particular, the user interfaces of web browsers prove vitally important to security given the sensitive nature of content provided by users—information spanning from banking to healthcare and everything in between.

Claude Shannon, widely regarded as the “father of the information age,” aptly summarized Kerchoff’s Principle of security through open design:

“The enemy knows the system.”

When applied to browser UI, it is our belief that this principle necessitates the UI be designed in such a fashion that imitation attacks—one website masquerading as another—must never be allowed to compromise or otherwise complicate user security.

Our preliminary literature review has uncovered a myriad of shortcomings in the user interfaces of web browsers, and we have concluded that these shortcomings generally fall into two distinct categories:

- Inability to easily discern between trusted and untrusted content

- Inability to easily validate website identities

During our review, we were quite surprised to discover an apparent dearth of academic literature specifically addressing web browser UI. Instead, much of the existing discussion is relegated to blog posts, security articles, and developer forums. We believe that the area of web browser UI poses a series of compelling questions deserving of dedicated analysis and research. To this end, we seek to coalesce, assess, and expand upon existing knowledge in this domain in order to effectively systematize knowledge for the benefit of future research work. It is our hope that this systematization of knowledge will shed light on unsolved challenges and provide a framework of prioritization that can guide researchers (and perhaps even ourselves) in improving security via better user interfaces in future work.

The State of Browser UI: Problematic

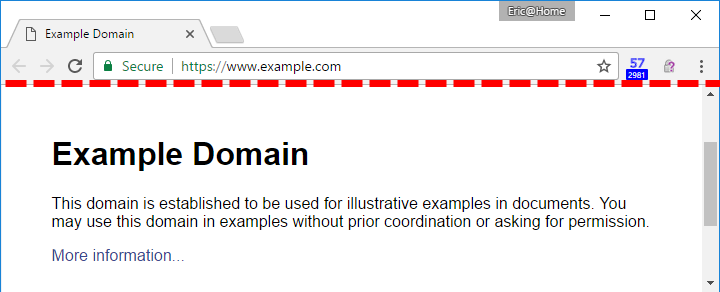

1) The Line of Death

The Line of Death (LoD) is a class of web browser attacks that target the very pixels of a browser UI on a given webpage, especially with regards to the (presumably) browser-controlled portion of the UI above webpage content.

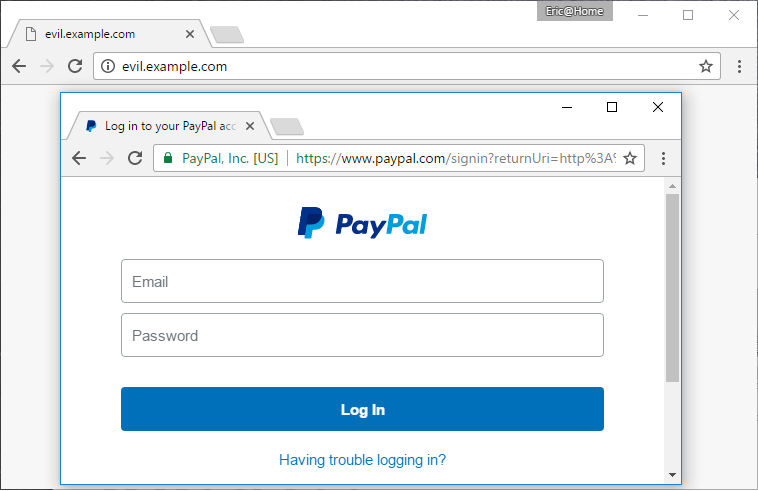

LoD attacks span the spectrum from manipulating URL names and tabs to spoofing new browser windows within the webpage’s content area:

Certified Malice is a phishing attack that deceives users into trusting a page that looks nearly identical to the real site, including TLS certificates with realistic naming schemes. This threat becomes even more potent if combined with URL pixel manipulation.

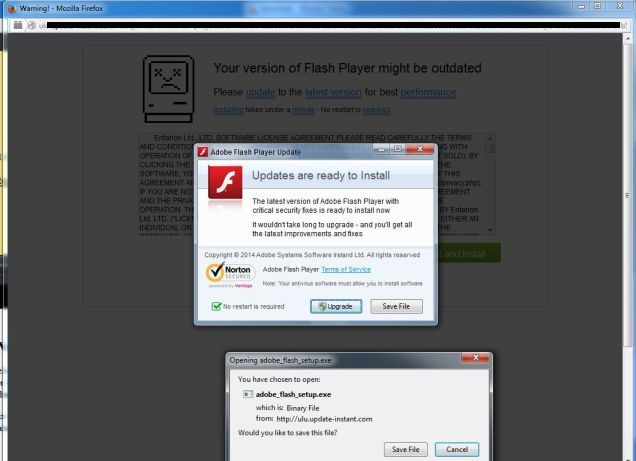

LoD attacks encompass more than just browser-object and URL spoofing attacks. Some attacks attempt to erode users’ abilities to discern legitimate OS prompts from spoofed prompts displayed in the browser, often designed to scare users into downloading or updating software. Advanced JavaScript and HTML5 features have effectively blurred the line between browser UI and dynamically generated (and hence untrusted) page content.

Given the broad range of LoD-inspired attacks that have surfaced in the past year, the Line of Trust project seeks to generate potential solutions that improve the level of security a browser provides when trusted UI pixels and browser notifications are compromised or forged.

2) Website Identity Validation and Verification

In September of 2016, Googler Owen Campbell-Moore posted a series of thoughts on browser UI titled “Rethinking URL bars as primary browser UI.” After consulting the Google Chrome team, he came to the contentious conclusion that the URL bar may be an anachronism in the reality of today’s Web, kept alive for the historical reason of “we’ve always done it that way.” He specifically identified three primary reasons why UI designers have retained the URL bar:

- So users understand who they’re talking to

- So users can know where on a site they are, and navigate by modifying the URL

- So users can share links to what they’re currently looking at

Campbell-Moore notes that today’s URL “omnibar” is responsible for far too many aspects of the browser UI to be effective (site identity, location within the site, security status, geographic location indicator, pop-up control, plug-in status) and argues that these constraints should be satisfied via alternative methods.

In essence, he offers that (1) and (2) are not compelling enough reasons to maintain the URL bar. In its place, he suggests establishing an origin-to-local-brand-mapping system, managed by search engines (presumably Google), that would serve to validate the identities of a certain subset of popular websites, displaying trusted identity information where the complicated URL omnibar is presently situated. (And, of course, this identity information would be unspoofable, much like how “www.facebook.com” belongs to Facebook and cannot be issued to anyone else.)

“When a user is on Facebook, why doesn’t the URL bar just say ‘Facebook,’ with a small Facebook logo? Would that not more clearly help the user understand the literal origin of the content? Clearly, we would need a way for browsers to determine the locally known brand name and logo of all sites.”

We believe that Campbell-Moore has raised a hugely important point, even if abolishing the URL bar may be infeasible:

If we were to redesign the web browser UI from scratch, how would we do it?

It is our hope that a potential answer to this question would effectively thwart all the aforementioned UI shortcomings.

Moving Forward

Given the shortcomings and opportunities for study identified above, we plan to investigate four areas in the realm of usable browser security: spoofing legitimate browser UI elements, picture-in-picture attacks, exact reproductions of websites, and full browser UI redesigns.

For each of these four areas, we will follow a specific system, defined below, for gathering and analyzing information.

First, we determine what past work has been done in that area, as well as relevant security problems.

Next, we examine old solutions to these early problems. These solutions patch and target specific types of attacks, and are very narrow in scope. Many of these solutions are therefore obsolete due to more recent changes in web usage, such as HTML5 and browser modifications. However, these new developments yield new problems within their respective areas.

We devise various potential unbounded solutions to these problems and categorize them into three types: UI solutions (which deal with user awareness), experimental techniques (solutions based on vision, NLP, and other cutting edge techniques), and infrastructure redesign (solutions that require more extensive change, potentially even beyond the browser).

Stage 1 is underway and will soon transition to stage 2. The target deliverable on April 28th is a quality SoK that will define the problem, provide our preliminary reasoning on the issues at stake, suggest some potential avenues to fix the problems, and conclude with open research questions. We intend to carefully reason about underlying connections among the UI issues that may point toward a common “best” solution.

Relevant Resources

The Line of Death - Text/Plain Details of spoofed browser prompts, untrusted and trusted information zones, and picture-in-picture attacks

Rethinking URL bars as primary browser UI Replace the browser URL bar with an “identity bar” managed by search engines, since “no one uses the URL bar anymore”

PetNames Associate a catchphrase with trusted websites in order to quickly identify fraudulent copies of the websites (evident if the catchphrase is absent)

Microsoft Support Page - LoD Attack Very recent LoD attack on the Microsoft Support Page; takes advantage of fullscreen HTML5

Verification Engine LoD defense mechanism c. 2006 that highlights the borders of trusted UI elements when the mouse hovers over them (could be mimicked with advanced JavaScript and HTML5 today)

SpoofGuard Tactics to defend against fraudulent websites c. 2004; most of the techniques are outdated now

TrustBar Suggests that “…a realistic usability test should provide a reasonable level of introduction of any new mechanism, balancing this with the risk of causing users to be overly-aware of security.”

Contributors

- Anant Kharkar, undergraduate student at the University of Virginia

- Sam Havron, undergraduate student at the University of Virginia

- Bill Young, graduate student at the University of Virginia

- Joshua Holtzman, undergraduate student at the University of Virginia

- Dave Evans, project advisor and computer science professor at the University of Virginia